If there’s one material that has stood the test of time — from ancient temples to modern ecological homes — it’s lime. Before cement became common, lime was the backbone of construction around the world. It was used in mortars, plasters, paints, and even waterproofing. And there’s a reason for that — lime is alive.

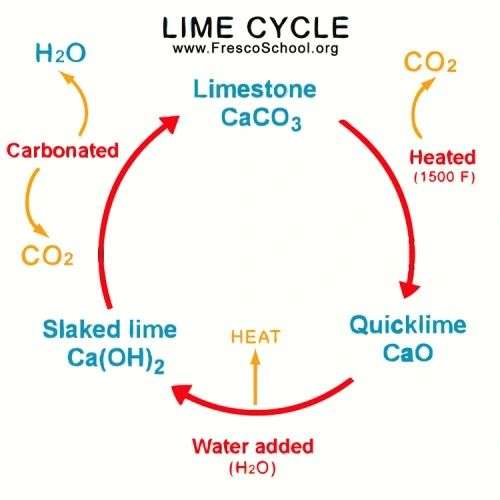

To work with lime, one must understand its cycle — the natural process through which it transforms and regenerates itself. The Lime Cycle is not just chemistry; it’s the story of transformation between the earth and the air, stone and life.

1. From Limestone to Quicklime (Calcination)

The journey begins with limestone, a rock rich in calcium carbonate (CaCO₃) — formed from the remains of marine shells and corals over millions of years. When limestone is heated in a kiln at around 900–1,000°C, it undergoes calcination, releasing carbon dioxide (CO₂) and turning into quicklime (calcium oxide, CaO).

CaCO3 (limestone) → heat CaO (quicklime) + CO2 (gas)

This is the first transformation — from stable stone to a reactive, high-energy material. Quicklime is extremely caustic and must be handled with care. This is where patience begins — you can’t rush lime.

2. From Quicklime to Slaked Lime (Hydration)

When quicklime comes in contact with water, it reacts vigorously — releasing heat and expanding. This process is called slaking, and the result is slaked lime powder or lime putty (calcium hydroxide, Ca(OH)₂).

CaO (quicklime) + H2O (water) → Ca(OH)2 (slaked lime)

The reaction looks simple, but the quality of this slaking process determines everything that follows. A good slake — slow and even — produces creamy, plastic lime putty that can last for years if kept submerged in water.

3. From Slaked Lime to Carbonated Lime (Setting and Hardening)

When you apply lime mortar or lime plaster, it doesn’t “set” like cement. It hardens by absorbing carbon dioxide (CO₂) from the atmosphere — a slow process called carbonation.

Ca(OH)2 (slaked lime) + CO2 (air) → CaCO3 (limestone) + H2O

Through this process, lime returns to its original stone form — calcium carbonate (CaCO₃). It literally recreates stone on your wall, one molecule at a time. That’s why lime is called a living material — it breathes, reacts, and regenerates.

This natural carbonation makes lime:

- Breathable – it allows moisture to escape, reducing dampness and mold.

- Flexible – it moves with the building without cracking.

- Self-healing – small cracks close as carbonation continues.

- Low-energy – it reabsorbs much of the CO₂ released during burning.

4. Completing the Cycle — Stone Again

When carbonation is complete, lime becomes limestone once again. The cycle has come full circle:

Limestone → Quicklime → Slaked Lime → Carbonated Lime → Limestone

This closed-loop process is nature’s perfect recycling system. If lime-based waste is left to weather naturally, it can rejoin the earth harmlessly. But when mixed with cement, polymers, or synthetic paints, this cycle breaks — turning a regenerative material into landfill waste.

Understanding and Patience: The Real Skill

Lime is not difficult — it’s just different. Each type of lime behaves differently depending on:

- Its source of limestone

- Burning temperature

- Slaking method

- Storage time

- Local humidity and temperature

To use lime well, you must understand your lime. You can’t rush it like cement. It needs time to cure, to breathe, to transform. Builders who are impatient often think “lime doesn’t work” — but it’s not the lime that fails, it’s our pace.

Lime, Landfills, and the Future of Building

Ironically, a material that can return harmlessly to the earth often ends up in landfills. Why? Because we mix it with incompatible materials. When lime is blended with cement or plastic paints, it cannot reabsorb CO₂ or biodegrade — it becomes inert waste. But if we respect the lime cycle, every bit of waste can be reabsorbed into the natural system — truly zero waste construction.

Lime reminds us that regeneration is not a concept — it’s chemistry, craft, and care working together.

Key Takeaways for Students and Builders

- Lime hardens by carbonation, not by drying. Give it air and time.

- Always slake quicklime properly. Poor slaking leads to failure.

- Keep slaked lime under water — it improves with age.

- Never mix lime with cement or synthetic additives — it breaks the natural cycle.

- Use breathable finishes. Lime paints, natural pigments, and oil coatings maintain breathability.

- Patience is not optional. It’s part of the process.

Final Reflection

The lime cycle is nature’s way of showing us that sustainability doesn’t need invention — it needs understanding. When you respect this cycle, you build not just strong walls, but living structures that breathe with the environment.

Lime’s secret is simple:

What it takes from the earth, it gives back.

What it releases, it reabsorbs.

That’s not just chemistry — that’s balance.

Hydrated Lime (90-95% Purity)

Our Hydrated Lime, available in Aged Putty and Powder Form, is sourced from reliable sources and boasts an impressive 90-95% purity. Ideal for lime plaster, brick masonry, and Hempcrete construction, this high-quality lime is durable, eco-friendly, and supports sustainable building practices.

Aged Putty remains fresh for extended periods when properly packed, while Powder Form offers flexibility for precise mixing and control.